Acceptance

tests are tests conducted to determine if the requirements of a

specification are met.

In modern software development, we call this specification, acceptance criteria.

In modern software development, we call this specification, acceptance criteria.

“Whenever

possible” it would be desirable to acceptance test, the system end

to end.

By end to end, I mean talking to the system from the outside, through its interfaces.

By end to end, I mean talking to the system from the outside, through its interfaces.

Note

that at the beginning of the previous paragraph, I said “Whenever

possible”.

The reason for this, is that it would be risky and also costly to integration test our code(against other code, we don't control/own). Sometime applications within a system, don't even belong to our company or they are too costly and slow to run. Because of this, the amount of system full stack tests/functional tests, should be very reduced/almost none.

The reason for this, is that it would be risky and also costly to integration test our code(against other code, we don't control/own). Sometime applications within a system, don't even belong to our company or they are too costly and slow to run. Because of this, the amount of system full stack tests/functional tests, should be very reduced/almost none.

In

acceptance testing we often start from an assumption about those

external systems we cannot control. The parts out of our control are

faked and the acceptance criteria, is aimed to those parts we

control.

When

writing an acceptance test, there is a commonly used format to

define the acceptance criteria. It is well known as the

“given,when,then” format:

- given: The setup/preconditions, of the scenario that we will test. Its contains what is that we expect from those remote systems(either internal or external) on which we depend.

- when:

Is the specific call to the exposed interface we are testing.

- then:

Is the validation of the results.

Today's

acceptance test are written with the help of live specification

frameworks, such as: Jbehave, Fit, Fitnesse, Concordion, Yatspec...

The use

out this tools, will make easier to both understand complex scenarios

and maintain criteria.

Understanding

Yatspec

Next I will talk about writing acceptance tests with a popular live

specification framework called Yatspec. I will explain some of its

features and describe the way it presents the test report. Also I

will explain with an example how we could stub systems out of our

control and use them in our acceptance test.

About

yatspec

-its a Live specification framework for Java(https://code.google.com/p/yatspec/)

-its a Live specification framework for Java(https://code.google.com/p/yatspec/)

-produces readable Html

-supports table/parametrized tests

-allows writing in given-when-then style

The

scenario

The application we will be testing, will receive a GET request from a

client, then it will send subsequent GET requests to two remote

systems(A and B), process the responses and POST the result to a

third system(C), just before returning it to the client.

The

criteria

-Given System A will reply 1 2 3

-And System B will reply 4 5 6

-When the client asks for the known odd numbers

-Then the application responds 1 3 5

-Then

'System C' receives 1 3 5

Creating

html reports

Before going in depth into our example, I want to expend some time

discussing how Yatspec reports look like, and what are the basics in

order to create them(If you want to go directly to the scenario

implementation, just skip this section).

When a Yatspec specifications are run, it will generate a html report. Advance options, can allow you to publish it remotely, but by default it will be written to a temporary file in the file system.

The terminal will tell you where it is like this:

Yatspec output:

When a Yatspec specifications are run, it will generate a html report. Advance options, can allow you to publish it remotely, but by default it will be written to a temporary file in the file system.

The terminal will tell you where it is like this:

Yatspec output:

/tmp/acceptancetests/KnownOddNumbersTest.html

We can navigate to it from the browsers

url:

file:///tmp/acceptancetests/KnownOddNumbersTest.html

file:///tmp/acceptancetests/KnownOddNumbersTest.html

Lets have a look at how it is structured:

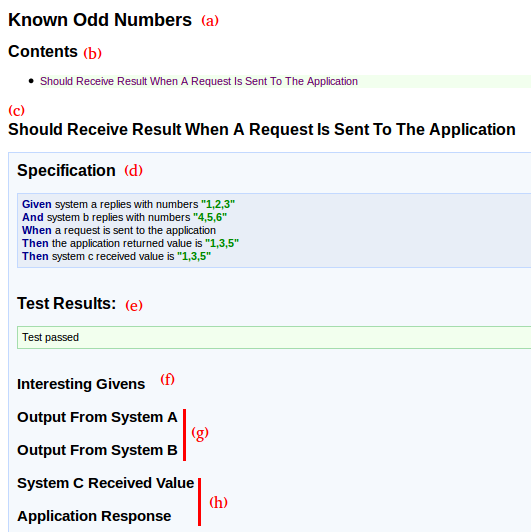

(a)

Is the title of the report. If Yatspec finds the postfix 'Test' on

the class name, it will remove it and just present the rest of the

title.

@RunWith(SpecRunner.class)

public class KnownOddNumbersTest extends TestState {

//Your tests

...

}

(b)

In the contents section you will see a summary of all the test

names(There can be multiple tests) in the same specification.

(c)This

is the test name. We

don't need to add any additional, anotations, all we need is to write

our test names in “camel case”. If

the test throws any exception, it will not be shown in the report.

@Test

public void shouldReceiveResultWhenARequestIsSentToTheApplication() throws Exception {

//Test body...

}

(d)

At the beginning of each test, the

criteria will

be presented. Yatspec will use the contents of the method body to

generate it. The methods given(), and(), when(), then() are

inherited from TestState.java(latter I will explain how to use them).

@Test

public void shouldReceiveResultWhenARequestIsSentToTheApplication() throws Exception {

given(systemARepliesWithNumbers("1,2,3"));

and(systemBRepliesWithNumbers("4,5,6"));

when(aRequestIsSentToTheApplication());

then(theApplicationReturnedValue(), is("1,3,5"));

then(systemCReceivedValue(),is("1,3,5"));

}

(e)

This is where test result

will be shown. Yatspec will colour this part in green if the test

passes , in red if the test fail or in orange it the test is not run.

(f)Interesting

givens are the preconditions for the test to run. This preconditions

are stored in the class TestState.java in an object called

interestingGivens. The way we would commonly do this by passing a

GivensBuilder object to the the method given(). Also the method and()

can be used to add more information in our interesting givens.

@Test

public void shouldReceiveResultWhenARequestIsSentToTheApplication() throws Exception {

given(systemARepliesWithNumbers("1,2,3"));

and(systemBRepliesWithNumbers("4,5,6"));

//...

}

private GivensBuilder systemARepliesWithNumbers(String numbers) {

return givens -> {

givens.add("system A returns", numbers);

return givens;

};

}

private GivensBuilder systemBRepliesWithNumbers(String numbers) {

return givens -> {

givens.add("system B returns", numbers);

return givens;

};

}

(g)

This are the captured inputs and outputs. Its purpose is to record

values that go in or out of any component

in the workflow.

TestState.java contains an object called capturedInputsAndOutputs to

which we can add or query from. Comonly we would indirectly add a

value to the capturedInputsAndOutputs to track the response of our

application so it can be verified latter, via a parameter of type

ActionUnderTest.java to the when() clause method.

@Test

public void shouldReceiveResultWhenARequestIsSentToTheApplication() throws Exception {

//...

when(aRequestIsSentToTheApplication());

//...

}

private ActionUnderTest aRequestIsSentToTheApplication() {

return (givens, captured) -> {

//The second object of this lambda is capturedInputsAndOutputs

captures.add("application response", newClient()

.target("http://localhost:9999/")

.request().get().readEntity(String.class));

return captures;

};

}

(h)

This are the final

verifications. They are created by the then() method. You will

distinguish if the output was generated by the then() method, because

it is not highlighted in yellow.

An StateExtractor.java is responsible for the values in this section. The state extractor will take from the captures the values that where recorded previously so a matcher can verify if they are correct.

An StateExtractor.java is responsible for the values in this section. The state extractor will take from the captures the values that where recorded previously so a matcher can verify if they are correct.

@Test

public void shouldReceiveResultWhenARequestIsSentToTheApplication() throws Exception {

//...

then(theApplicationReturnedValue(), is("1,3,5"));

}

private StateExtractor<String> theApplicationReturnedValue() {

return captures -> captures.getType("application response", String.class);

}

}

The

scenario implementation

Now

that we understand the criteria and we have some basic understanding

of Yatspec reports. Lets

write an acceptance test for the criteria described before.

In

our scenario System A, B and C are out of our control(Lets imagine

they are owned by companies). We need to first query A and B and

then send the processed result to C before replying to the client.

This means that our interesting givens will be the values returned from A and B and our captured inputs and outputs will contain the input into C.

This means that our interesting givens will be the values returned from A and B and our captured inputs and outputs will contain the input into C.

So

let's have a look at how Systems A and B return the values previously

saved in the interesting givens to the application and also how

System C captures the input.

For

this example, I created a class called FakeServerTemplate.java which

contains the boiler plate code that is necessary to create an

embedded server. Each System A, B and C will inherit from it and

provide specific handler implementations.

public abstract class FakeSystemTemplate {

private final HttpServer server;

protected InterestingGivens givens;

protected CapturedInputAndOutputs captures;

public FakeSystemTemplate(int port, String context,InterestingGivens givens, CapturedInputAndOutputs captures) throws IOException {

this.givens = givens;

this.captures = captures;

InetSocketAddress socketAddress = new InetSocketAddress(port);

server = HttpServer.create(socketAddress,0);

server.createContext(context, customHandler());

server.start();

}

public abstract HttpHandler customHandler();

public void stopServer() {

server.stop(0);

}

}

Latter,

when we create the acceptance test we will see how we will pass the

interesting givens and the captured inputs and outputs to the

Systems.

Systems

A and B will return the values stored in the interesting givens using

a unique key(Latter we will see how this keys are set in the givens).

public class SystemA extends FakeSystemTemplate {

public SystemA(int port, String context, InterestingGivens interestingGivens, CapturedInputAndOutputs capturedInputAndOutputs) throws IOException {

super(port, context, interestingGivens, capturedInputAndOutputs);

}

@Override

public HttpHandler customHandler() {

return httpExchange -> {

String response = givens.getType("system A returns", String.class);

httpExchange.sendResponseHeaders(200, response.length());

OutputStream outputStream = httpExchange.getResponseBody();

outputStream.write(response.getBytes());

outputStream.close();

httpExchange.close();

captures.add("output from system A", response);

};

}

} public class SystemB extends FakeSystemTemplate {

public SystemB(int port, String context, InterestingGivens interestingGivens, CapturedInputAndOutputs capturedInputAndOutputs) throws IOException {

super(port, context, interestingGivens, capturedInputAndOutputs);

}

@Override

public HttpHandler customHandler() {

return httpExchange -> {

String response = givens.getType("system B returns", String.class);

httpExchange.sendResponseHeaders(200, response.length());

OutputStream outputStream = httpExchange.getResponseBody();

outputStream.write(response.getBytes());

outputStream.close();

httpExchange.close();

captures.add("output from system B", response);

};

}

}

For

system C we will be capturing the arriving input.

public class SystemC extends FakeSystemTemplate {

public SystemC(int port, String context, InterestingGivens interestingGivens, CapturedInputAndOutputs capturedInputAndOutputs) throws IOException {

super(port, context, interestingGivens, capturedInputAndOutputs);

}

@Override

public HttpHandler customHandler() {

return httpExchange -> {

Scanner scanner = new Scanner(httpExchange.getRequestBody());

String receivedMessage = "";

while(scanner.hasNext()) {

receivedMessage += scanner.next();

}

scanner.close();

httpExchange.sendResponseHeaders(200, 0);

httpExchange.close();

captures.add("system C received value", receivedMessage);

};

}

}

Now

that our remote systems are ready, lets write our test.

@RunWith(SpecRunner.class)

public class KnownOddNumbersTest extends TestState {

private SystemA systemA;

private SystemB systemB;

private SystemC systemC;

private Application application;

@Before

public void setUp() throws Exception {

systemA = new SystemA(9996, "/", interestingGivens, capturedInputAndOutputs);

systemB = new SystemB(9997, "/", interestingGivens, capturedInputAndOutputs);

systemC = new SystemC(9998, "/", interestingGivens, capturedInputAndOutputs);

application = new Application(9999, "/");

}

@After

public void tearDown() throws Exception {

systemA.stopServer();

systemB.stopServer();

systemC.stopServer();

application.stopApplication();

}

@Test

public void shouldReceiveResultWhenARequestIsSentToTheApplication() throws Exception {

given(systemARepliesWithNumbers("1,2,3"));

and(systemBRepliesWithNumbers("4,5,6"));

when(aRequestIsSentToTheApplication());

then(theApplicationReturnedValue(), is("1,3,5"));

then(systemCReceivedValue(),is("1,3,5"));

}

}

By

extending TestState.java we get acces to the interestingGivens and

capturedInputsAndOutputs objects. We will pass them to the remote

systems, this way Systems A and B will be aware of what we expect

them to return and also C will be able to capture its input.

The

methods used inside given(), and(), when() then() are just static

fixture methods. I think it good to avoid making long classes so

that's why the test class just contains the test, everything else is

extracted into reusable fixture methods. Lets have a look at them.

public class GivensFixture {

public static GivensBuilder systemARepliesWithNumbers(String numbers) {

return givens -> {

givens.add("system A returns", numbers);

return givens;

};

}

public static GivensBuilder systemBRepliesWithNumbers(String numbers) {

return givens -> {

givens.add("system B returns", numbers);

return givens;

};

} public class WhenFixture {

public static ActionUnderTest aRequestIsSentToTheApplication() {

return (givens, captures) -> {

captures.add("application response", newClient().target("http://localhost:9999/").request().get().readEntity(String.class));

return captures;

};

}

} public class ThenFixture {

public static StateExtractor<String> theApplicationReturnedValue() {

return captures -> captures.getType("application response", String.class);

}

public static StateExtractor<String> systemCReceivedValue() {

return captures -> captures.getType("system C received value", String.class);

}

}

Once we

run the application, the acceptance test would go red, the next thing

to do if we were parcticing ATDD, would be to go into the production

code and write unit tests to guide the creation of the code that is

required to make the acceptance go green. Remember the ATDD cycle.

The TDD

of the final solution is out of the scope for this blog post, but you

can find all the completed codes at this git repo:

No comments:

Post a Comment